Literature reviews for undergraduates

A literature review is like a guided tour through what other researchers have said about a topic. It helps you evaluate, classify, and present existing ideas so you can build your own. Want to know how to structure one? Let’s walk through it.

A literature review helps you present, classify and evaluate what other researchers have written about a topic. It’s not just a 'shopping list' of sources, it’s a structured overview shaped by your research objective, research question, and/or the problem/issue you’re exploring.

With a clear focus, your review becomes a roadmap of what’s already been done in the area you’re investigating.

Why do a literature review

Surveying and evaluating the literature that has already been written on a subject provides context for your own research. It enables you to clarify and sharpen your own research focus and methodology. Evaluating each publication by reviewing it can also clarify what has been established with a degree of certainty, and what is considered acceptable research work in a given field of study.

What is literature

Literature refers to all the texts and works concerning a particular topic. If you’ve been asked to do a literature review on the history of the Aztecs, the literature refers to any books, journals, conference papers, letters or documents or other pieces work about (or by) the Aztecs. Literature is generally divided into primary, secondary and tertiary sources.

Literature sources

Decide how many references to use

The number of sources you need depends on your level of study and the topic itself. A 'hot' topic in an area of cancer research for a PhD student might require keeping abreast of hundreds of research publications a week. A 'cold' topic such as St Anselm’s third version of the ontological argument for God’s existence, might have a very limited range of research publications worldwide, and no recent publications.

As a general guide (check with your lecturer):

- Undergraduate review: 5-20 titles depending on level

- Honours dissertation: 20+ titles

- Masters thesis: 40+ titles

- Doctoral thesis: 50+ titles

Know what your aim is

If you are writing a thesis or dissertation, the aim of writing a literature review is to understand the context of your own research by surveying and evaluating what has already been written on the topic. Surveying the literature can enable you to clarify your own focus and methodology. Evaluating each publication can also clarify what are considered valid and important areas in your field of study.

Crucially, a literature review helps to establish the research gaps in a particular area and, in so doing, outlines areas that require further research and investigation. When reviewing literature, you refer to what others have written or done on a topic and compare and contrast the work of others. Your aim is to find a gap: i.e., what others have done and what needs to be done in your particular area of study. The literature review puts this gap into focus. Filling the gap is what you then go on and do in your research.

Narrow your focus

Narrowing the focus of the literature review is vital. It is not easy to find a gap in a research area such as: 'Computer crime.' The area is too vast.

However, if you were reviewing literature on 'Embezzlement via the use of targeted malware attacks on global supply chains of conglomerates in the footwear and clothing industry,' you might have more luck.

This is because your narrow area will have a limited range of research papers to investigate, and there are more likely to be discernible gaps. In general, being narrowly focussed is a good thing for research projects and literature reviews.

Structuring a review

The structure of a literature review is very similar to an essay with an Introduction, Body and Conclusion. However, there is more detail in terms of one’s analysis of the literature compared to a standard essay. There is also important links between what is set up in the Introduction and what is delivered in the Body.

Note: For an undergraduate literature review not everything listed here is expected.

Developing a writing taxonomy

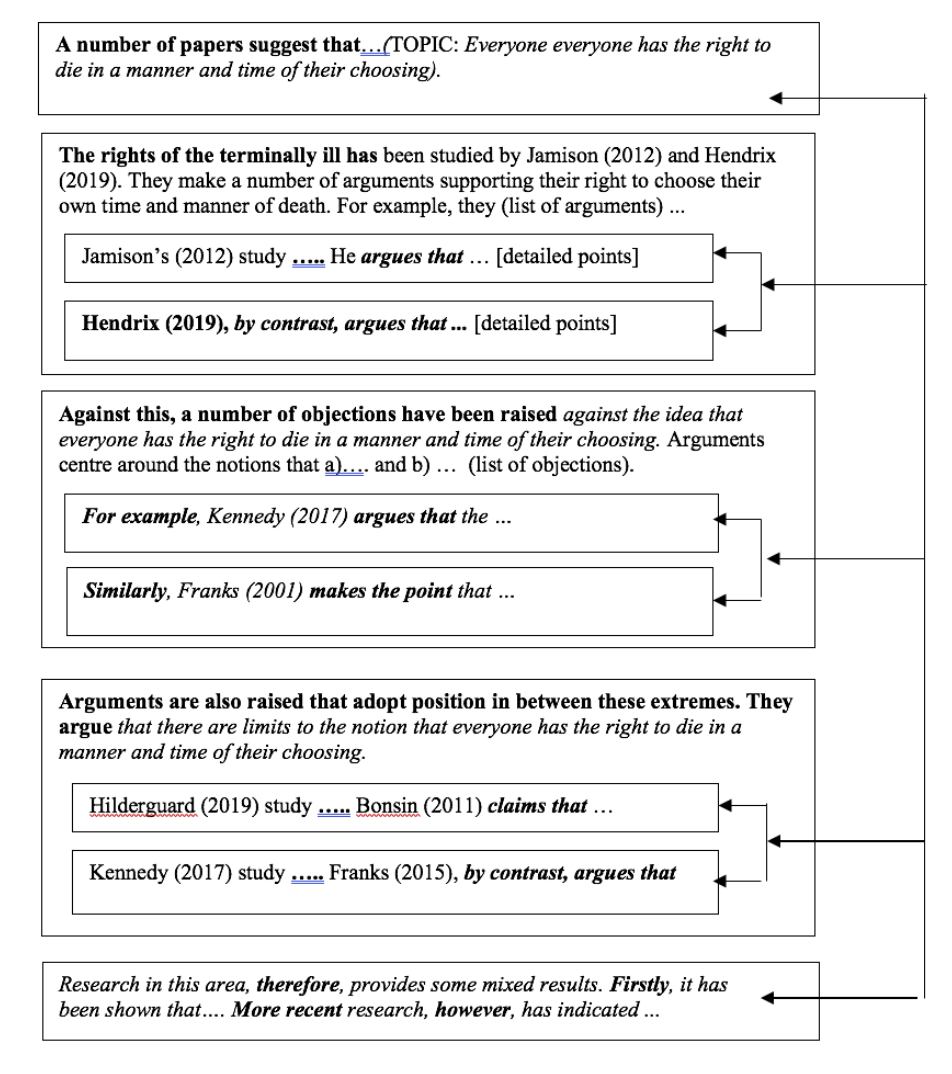

Designing an outline that gives shape to your literature review can help in the process of writing one. Attempts have been made to develop writing taxonomies (Rochecouste, 2005). A good way to think of this is as a series of nested categories with ‘vertical’ and ‘horizontal’ axes. An example of an outline on the topic of Euthanasia is provided below.

The first box represents the Introduction that sets the scene. The last box sums up the debates. The body content is in the boxes in-between. Of course, this is simple for the purposes of elucidation.

The ‘vertical’ categories (the “outer” boxes) are:

-

- Literature supporting euthanasia,

- Literature in opposition to euthanasia, and

- Literature supportive/against euthanasia, but with reservations.

They are ‘vertical’ because they add new content ideas to advance the discussion.

The ‘horizontal’ categories (the “inner” boxes) are various arguments or evidence-based considerations for each position. They are ‘horizontal’ as they essentially “fill out” examples of the positions articulated in the vertical boxes.

You now have the beginnings of a literature review! It is merely a matter of filling in the details.

Of course, this kind of outline can be expanded infinitely, as needed depending on the complexity of the review.

Reporting on literature

There are a number of ways to group literature and report on it when writing a literature review. It’s essential to do this. Writing without structure just leads to a big mess of ideas.