Why the frequency and intensity of Australia’s extreme weather events is changing

A warming atmosphere is leading to more lightning and thunderstorm events. Image: harvepino - stock.adobe.com

With January the hottest ever recorded globally, Australia has experienced another volatile start to the year that has seen extreme heat and bushfires in Victoria and record-breaking rainfalls in the northern states.

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) reported that last month was 1.75°C above the pre-industrial level and 0.79°C above the 1991-2020 average, despite expectations that a La Nina weather pattern could bring cooler temperatures.

The Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) reported that Victoria's January mean maximum temperatures were in the highest 10 per cent of all years since 1910, with rainfall well below average. In New South Wales and Northern Queensland, the start of 2025 saw flooding and severe damage, which extended into February.

Federation climate scientist Associate Professor Savin Chand says while extreme weather events have always been common in Australia, new research is revealing that the frequency and intensity of these potentially destructive events is changing.

"Australia is the land of extremes, often with heat, heavy rain and strong winds at the same time but in different parts of the country, and this has likely happened for millennia. But we have only had comprehensive records of weather variables extending back about 150 years," Assoc Prof Chand said.

"Temperature records and rainfall-over-land monitoring has been good since around 1900, and globally, the number of monitoring stations have increased since the end of World War 2, so there was a big increase in the number of observational records for climate trend analysis."

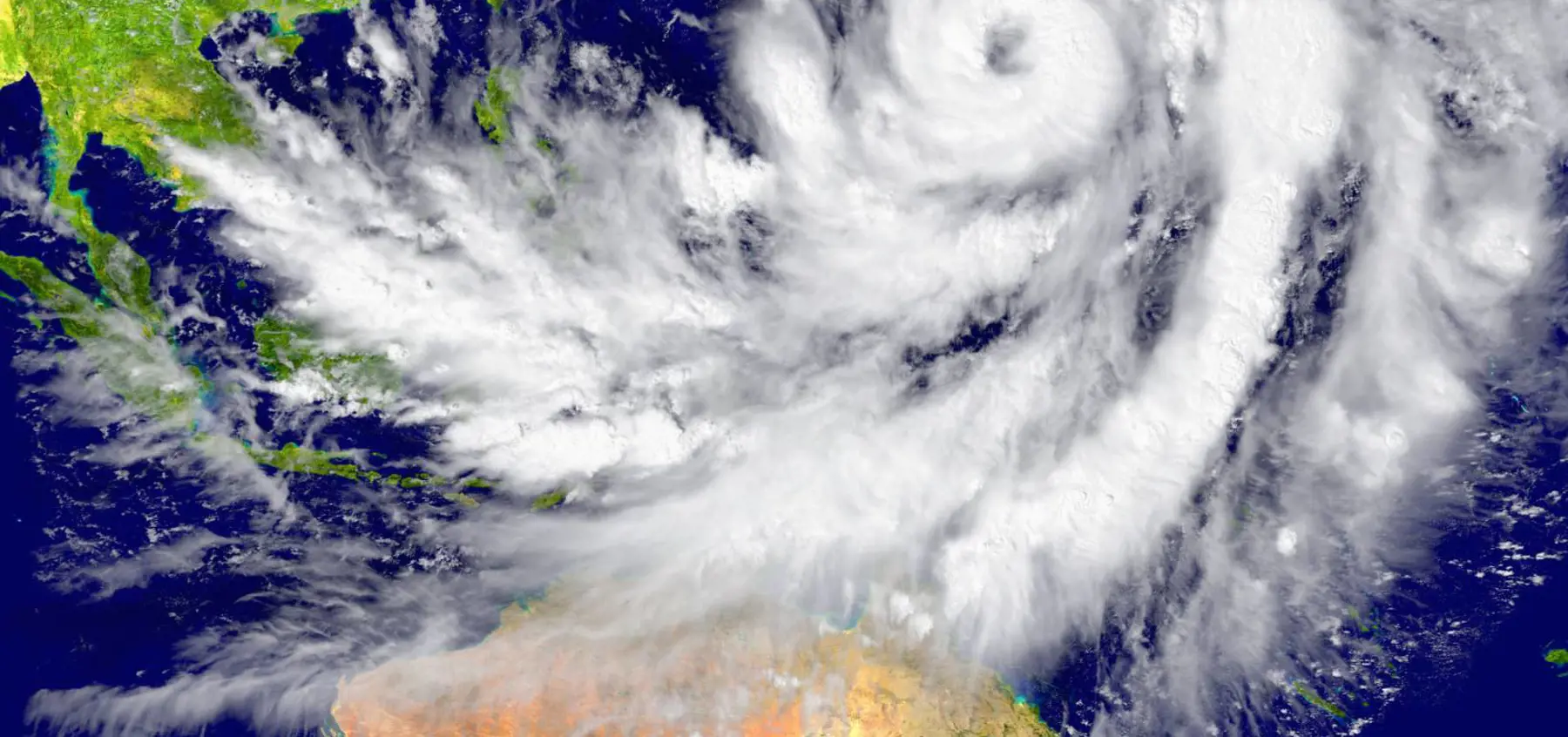

With satellite technology taking off in the 1960s and 1970s, Assoc Prof Chand says the improved records of weather variables have given climate scientists a much better understanding of extreme weather events and how these have been changing because of human-induced warming of the earth's atmosphere.

"Various drivers in the atmosphere account for the year-to-year variations in weather events. In Australia, the El Nino Southern Oscillation, for instance, tends to lead to drier conditions and the chances of bushfires increase," he said.

"But over the past three years, there have been more La Nina conditions, which generally see more rain and convective events like tropical cyclones and thunderstorms. On top of normal variability, we're beginning to see a trend which we can say with confidence that global warming is impacting these extremes.

"Different extremes get impacted differently. There have always been heatwaves – high temperatures over land – but we are getting heatwaves more often and they are becoming more intense. More days of the temperature hanging around or over 40°C for an extended period."

Assoc Prof Chand says while high temperatures don't necessarily translate into bushfires because there needs to be an ignition source, a warming atmosphere is leading to more lightning and thunderstorm events. These can strike in the form of dry lightning, which occurs in thunderstorms that produce little to no rain and are of significant risk to bushfires in states like Victoria and NSW, as there is no rain to put out sparks.

Further north, where heavy rainfall is typical over summer, Assoc Prof Chand says these events are also becoming more severe.

When ex-tropical cyclone Jasper stalled over the Townsville area in December 2023, it became the wettest tropical cyclone in Australian history. It included a five-day total of 2,166mm at Bairds near the Daintree River, causing significant damage to properties and industries while isolating communities.

Even weaker low-pressure systems, like those recently in Queensland, can effectively channel moisture from the ocean and dump huge amounts of rain, Assoc Prof Chand says.

Assoc Prof Savin Chand is working on an international project funded by the Gallagher Research Centre, established within its Global Tropical Cyclone Research Consortium, to carry out a comprehensive scientific assessment of tropical cyclones, such as Jasper, and associated rainfall for Australia and the Asia-Pacific.

The multi-year project will see Associate Professor Chand expand on his research into tropical cyclones in the region, including around several Asian countries, the South Pacific and Australia. His research shows that while the number of tropical cyclones is going down globally, the intensity of these developed systems is increasing.

His research is also looking at weaker weather systems – the lows and depressions often accompanied by monsoons that account for high levels of rain.

"We recently had a couple of low-pressure systems sitting over Queensland that have caused a huge amount of rainfall," Assoc Prof Chand said.

"Now the question is again the role of climate change here. Of course, we have warmed up the atmosphere, and there is a lot of moisture sitting in it – it's effectively a kind of reservoir that we have supercharged.

"Generally, we expect tropical cyclones and low-pressure systems to come over land and then go away. But now, low-pressure systems coming over land have effectively extracted moisture from the ocean – which is already warmer – and increased the rainfall amount locally.

"These low-pressure systems often stall – they hang around a lot longer – and that's when we have extended periods of heavy rain.

"The events are not uncommon in recent history, but the behaviour is changing, and we know this is because of a warming climate."